The Woman at The Well

One day in 1914, a young woman sat beside the well named for St Kentigern in the depths of Glasgow Cathedral. She was poorly dressed and carried a child in her arms. A victim of what we’d now acknowledge as domestic violence, she had come to the “guid well” to wish, or pray, for kindness.

Two gentleman antiquarians were visiting the church to sketch the well. One of them spoke to her — sympathetically, we must hope. His friend was more interested in what he would interpret, and describe in a paper, as a survival of pagan well-worship.

We don’t know that woman’s name or what she believed. Perhaps without realising it, she had brought her unseen desperation to an almost unseen place, a thin fracture full of silence in the story of the city and its saint.

*

The head of the Cathedral well is built into the masonry of the thirteenth-century wall, near the south-east corner of the lower church. The shaft is about three feet wide and eighteen feet deep; it is circular and lined with sandstone blocks, shaped to the curve of the wall and scored with occasional masons’ marks. At the bottom it is sealed by a layer of concrete or cement, with hints of rubble lying below. Today the well is almost always dry, though some water seeps in after heavy rain. And that is all we know about it for sure.

By the time the well entered the written record, in the mid-nineteenth century, its early history was lost. The Cathedral had been neglected for centuries, and the lower church served for some time as an unofficial crypt. Even the saintly dedication is uncertain: earlier mentions of “St Mungo’s Well” refer to the one at Little St Mungo’s, which later served the Saracen’s Head Inn. What more can we tentatively say?

*

There were other wells nearby. Across the Molendinar gully, the Lady Well drew its slightly sulphurous water from the rocks of Fir Park, now the Necropolis. Just above the burn itself was a small spring known as the Priest’s or Minister’s Well; it was lost when the Molendinar was culverted under Wishart Street. The mediaeval Bishop's Palace immediately to the west of the Cathedral had several wells, and a few hundred metres to the north the Howgait well — in use until the early nineteenth century — was 42 feet deep and stood “brimful” of water.

The Cathedral and its surroundings sit on boulder clay, up to about ten metres thick; below that are layers of sandstone, of varying permeability and thickness. The Palace well seems to have been sunk through the clay to tap a water-bearing layer, perhaps the same one that cropped out in the gully at the Priest’s Well. We can guess that the Cathedral well drew from the same source as its neighbours; but where did the water in that aquifer come from?

Today the bottom of the well lies roughly on a level with the tarmac of Wishart Street. The old Molendinar lay at least six feet below that, too low to charge the aquifer. Just above the Bridge of Sighs, however, there was a dam which supplied a mill-lade. We know from the Molendinar’s name that it was a mill-stream when the Life of St Kentigern was written, two generations before the current Cathedral was built. If the well is only as old as the Cathedral, it might ultimately have been fed by that dam. If it is as old as Kentigern, it seems more likely that the aquifer was fed by the slow infiltration of rain through the clayey soil, across a catchment that extended north- and westward of the well. Our guesses at its origin must shape our guesses at its source.

*

The wellhead seems to be contemporary with the wall of which it’s part. Presumably the well shaft pre-dated that wall; why sink it there, rather than within the building, otherwise? If that’s the case, the well stood outwith the first, twelfth-century cathedral. Perhaps it even served the monastic site, if there was one, that preceded the cathedral — the cemetery traditionally consecrated by St Ninian and “girded with a delightful thickness of overhanging oak trees”.

There is a mystery here. To be preserved while the Cathedral was being raised, that well must surely have been important. We might speculate that it was linked to the cult of St Kentigern: perhaps that, like St Patrick’s Well in Dublin, it was believed to be where he baptised his converts. Against this is an absence: there is no mention of a well in the Life written at Bishop Jocelyn’s behest to put the saint’s cult on a solid footing. If the well was ritually important, why did it have no story?

Wells can be found in other mediaeval churches: Dunfermline Abbey; Carlisle Cathedral; both York and Beverley Minsters. Perhaps the closest parallel is the church of St Oswald at Kirkoswald, Cumbria, where the well is built against the west wall. Little is known about any of these wells, and none was treated with particular respect. By Victorian times, St Peter’s Well at York had been converted, unsentimentally, into a pump.

*

St Kentigern’s shrine was a place of veneration and of pilgrimage for centuries, but the scattered evidence that survived the Reformation is silent about his well. This might not be strange. The Church hierarchy had an uneasy relationship with saints’ wells, which formed part of the rich, and sometimes subversive, culture of folk Catholicism — a culture in which rituals could be invented and reimagined, in ways that were rarely “pagan” but also rarely deferred to approved theology. Perhaps the Cathedral well was used, as some have speculated, for liturgical purposes such as baptism or ablution, either at the neighbouring altar of St John Evangelist or at St Kentigern’s shrine itself. Perhaps it was only used, as others have suggested, to draw water to wash the floor.

With the Reformation, official unease became open hostility. Going in pilgrimage to “chapels, wells, crosses and such other monuments of idolatry” was considered superstitious: a defiantly Catholic practice. It was proscribed by Parliament in 1581 alongside other “popish rights”; again by the Privy Council in 1629, in an order mostly directed against Jesuits; and yet again in the Act of 1700 “for preventing the growth of popery”. Some traditional holy wells were targeted by their local presbyteries, but the Cathedral well, safe within an ecclesiastical building, must have been beyond public access or presbyterian concern.

Despite their suppression, pre-Reformation habits lingered. In Glasgow, the votive tree by St Thenew’s Well remained into the eighteenth century; some of the offerings that once hung upon it were found when the well was cleaned out around 1800. Elsewhere in Scotland, traditions of healing rituals at particular wells survived into the late nineteenth century. It feels suggestive that these rituals were often performed by women, usually from the working classes. People with no official voice might still take their needs to a well, a source of life, hoping for unspoken, unofficial aid.

*

As the land to the north and west was covered and built up, or perhaps when the Molendinar dam was removed, the aquifer that supplied the well was starved of water. At some point — perhaps when the lower church was restored in the 1830s — its base was sealed. It is now fed only by local leakage through the clay. A “dreary drip, drip” from the well was a familiar sound a century ago, when the water table sometimes rose to ground level and newly dug graves could fill with water overnight. After heavy rain, water now stands in the well for two or three days at most.

Archaeologists exploring the well in 2025 removed several kilograms of modern coins from the sludge at the bottom, along with the remains of two pairs of spectacles and a tantalising fragment of stone. Broken and bearing a pattern of chisel marks, it also showed a hint of coloured paint. A stray piece of rubble from below the seal; perhaps even a relic of painted stonework shattered when the altars were torn down?

The stone remains silent.

*

The Cathedral well, then, may be older than Glasgow, left dry by the very city that was built around it, wetted only by leaking rain.

Rather than looking for an unbroken story that leads back to our legendary founder, perhaps we should listen for echoes, in an empty place where invisible people brought their unacknowledged prayers.

Perhaps we can offer it our need for stories, and draw them up from it anew.

Notes and sources

The Cathedral well is described in three antiquarian papers, which seem to be the ultimate source for most subsequent descriptions and interpretations.

J. Russel Walker, “Holy Wells” in Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 17: 152-210, 1883.

Alexander Fowler, Old draw and dip wells. Transactions of the Old Glasgow Club 3(1): 49-55, 1914.

T. C. F. Brotchie, The holy wells in and around Glasgow. Transactions of the Old Glasgow Club 4(1919-20): 66-75, 1920.

Brotchie gives the most detailed account, including the story of the young woman. Unfortunately he also muddles his sources (e.g. it was an “idolatrous well” in Dumfries, not Glasgow, which was proscribed in 1614).

There are also brief mentions of the Cathedral well in

George Eyre-Todd (ed.), The Book of Glasgow Cathedral. Morison Bros., Glasgow, 1898.

P. Macgregor Chalmers, The Cathedral Church of Glasgow. Bell & Sons, London, 1914.

A good description of the construction of the Cathedral and its predecessors is given in Richard Fawcett’s introduction to Medieval Art and Architecture in the Diocese of Glasgow (British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions XXIII, 1998); this clearly indicates how the site of the well lay outside the building until the middle thirteenth century. In the same volume, A. A. M. Duncan, St Kentigern at Glasgow Cathedral in the Twelfth Century, discusses the development of Kentigern’s cult; Stephen T. Driscoll, Highlights of the excavations at Glasgow Cathedral 1992-93, includes the archaeological evidence for the burial site that preceded the Cathedral. The altars of the lower church are catalogued by John Durkan, Notes on Glasgow Cathedral, Innes Review 21: 46-76, 1970.

There are descriptions of the Priest’s Well and the Lady Well in George Blair, Biographic and descriptive sketches of Glasgow Necropolis (Glasgow, 1857).

The Priest’s Well is marked on the 1857 Ordnance Survey 25-inch map of Glasgow, and the original location of the Lady Well on McArthur’s town plan (1778).

One of the Palace wells is described in West of Scotland Archaeology Service report WoSASPIN 9388 [http://www.wosas.net/wosas_site.php?id=9388].

The Howgait well is described by James Cleland, Annals of Glasgow (James Hedderwick, Glasgow, 1816).

For background information about pre- and post-Reformation attitudes to well worship, I’ve used Janet Bord, Sacred waters: holy wells and water lore in Britain and Ireland (Granada, 1985). However, I’ve followed Ronald Hutton's interpretation of “pagan” practices in mediaeval culture: see e.g. Ronald Hutton, How Pagan Were Medieval English Peasants? Folklore, 122(3): 235-249, 2011.

The official proscriptions of wells are from

Act of Parliament, 24 October 1581: Against passing in pilgrimage to chapels, wells and crosses, and the superstitious observing of diverse other popish rights.

Order of the Privy Council of Scotland, 25 July 1629.

Act of Parliament, 29 October 1700: Act for preventing the growth of popery.

I’ve quoted Cynthia Whidden Green’s translation of Jocelyn’s Life of Kentigern (MA thesis, University of Houston, 1998).

For the geology of the area near the Cathedral I’ve used British Geological Survey borehole data. My estimate of the level to which the Cathedral well reaches is based on Fowler’s statement of the depth and on my own amateur surveying efforts. It is hard to be sure of the exact level of the pre-culverted Molendinar, but comparing the Ordnance Survey 25-inch maps of 1857 and 1892-4 suggests that Wishart Street was at least six feet above the stream; pictures of the Bridge of Sighs before culverting support this.

I am also grateful to Colin Campbell (Friends of Glasgow Cathedral) for letting me blather and for telling me about the current condition of the well, and to Clyde Archaeology and Aproxima Arts for letting me potter around and gratify my curiosity when the well was being investigated in October 2025.

David Pritchard

Support The Well

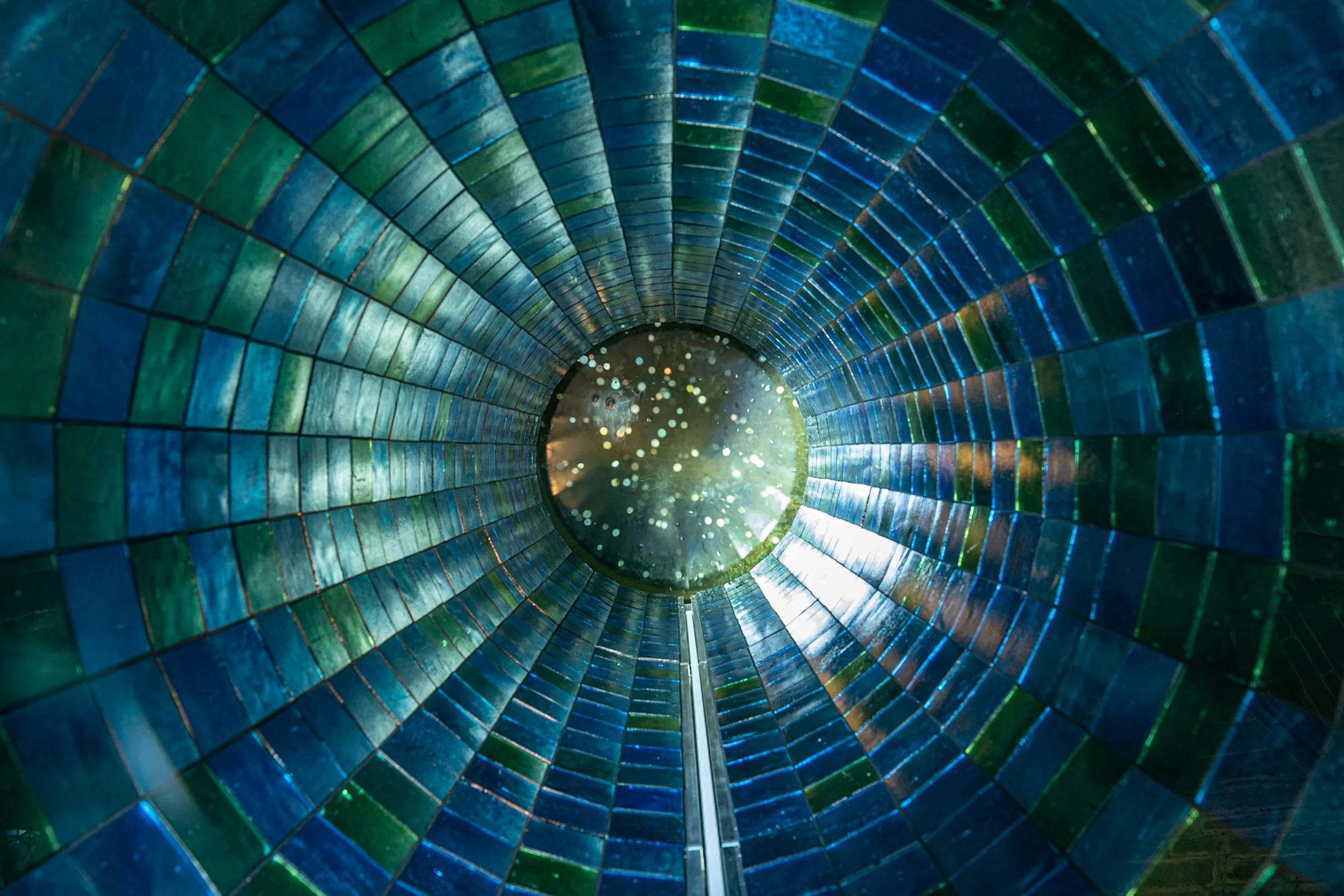

The mosaic has been designed to last for centuries. If you have enjoyed your visit to Glasgow’s Wellspring please support us with a donation of anything you can spare. We are a small charity and would really value the support to maintain this beautiful artwork into the future!

Funders

The Well is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the William Grant Foundation, the Mickel Trust, Glasgow City Heritage Trust, The Tom Farmer Foundation, The Robin Leith Trust, The Mercers’ Company, The City Charitable Company, Robin Hardie, Andrew Mickel, Mary Ann Sutherland, The Hope Scott Trust, the Hugh Fraser Foundation, Cockaigne Fund, City Centre Improvement Grant Fund and the William Syson Foundation.